Stunning designs by architect S.V. Lipgart.

Enjoy! Continue reading

Apparently rejected by Jacobin, this was originally posted over at Krul’s Notes and Commentaries blog.

In his recent essay on Jacobin, Seth Ackerman makes a number of common arguments in favor of some form of market socialism over and against central planning as well as other designs for non-market, non-capitalist economies. The essay contains much that most socialists could agree with. He rightly cites the failure of the neoclassical argument for general equilibrium to apply in real-world situations under the devastating theoretical impact of the Cambridge capital critique and the so-called ‘theory of the second-best’, and the lack of statistical evidence proving the superior efficiency of market capitalist societies over those of the former Soviet bloc. The historical record of capitalism to achieve general efficiency, equity, and democracy is, in short, atrocious, and neoclassical economics always serves first and foremost as apologetics for this system – we probably need not go into this further.

Also understandable is Ackerman’s negative response to models of a post-capitalist economy along the lines of some form of direct democracy, such as Albert and Hahnel’s “Parecon” approach. For Albert and Hahnel, democratic councils would gather data from individuals regarding their preferences, debate these according to socialist and ecological norms, and process them into a planning system, which would regularly update its information according to the same political processes; all this in order to regulate production for human need. Ackerman is justifiably skeptical of the workability of this proposal, as it would require millions of political debates about millions of input-output processes from wildly divergent sources and for wildly divergent ends. If every aspect of the planning system would have to be truly democratic – in the sense of being up for immediate political input ‘from below’ – any system with more than a rudimentary division of labor would quickly come to a shuddering halt.

For Ackerman, this is proof of the validity of the so-called calculation problem, an old argument from liberal critics of Marxism (in particular the Austrian school of economics), alleging that it is a priori impossible for centrally planned economies of any kind to operate: only prices, the argument runs, are accurately able to convey the necessary decentralized and distributed information that makes up the relative exchange value of goods. Therefore, in any system seeking to replace prices (and by implication, profits) with some form of central management, there necessarily follows a shortage of information in the decision-making process in production and exchange, with the familiar results of shortages, gluts, famines, and failures of supply. Continue reading

IMAGE: Ivan Kudriashev, Construction

of a Rectilinear Motion (1925)

Continuing this metaphor, common to both Nietzsche and Marx, we might still ask: What is it, exactly, to which “old collapsing bourgeois society” is giving birth? Nietzsche saw two possibilities, depending on whether the self-overcoming of the present had been borne “[of] a desire for fixing, for immortalizing, for being, or rather [of] a desire for destruction, for change, for novelty, for future, for becoming.” If the former, Nietzsche warned, the impulse is romantic and regressive, an attempt to return to the static existence of tradition. “The desire for destruction, for change and for becoming,” by contrast, “can be the expression of an overflowing energy pregnant with the future.”[72] Once more, the present’s pregnancy with the future is intimately bound up with the problem of conscience and self-becoming. As Nietzsche indicated in The Gay Science: “What does your conscience say? — ‘You should become who you are.’”[73] How is this accomplished? Through boundless negativity, through a fearless commitment to self-transformation, by embracing “the eternal joy in becoming, — the joy that includes even the eternal joy in negating…”[74]

In a similar fashion, Marx understood the bourgeois epoch to be characterized by perpetual flux, the annihilation of existing conditions to make way for those arising out of them: a ceaseless motion of becoming. Materialist dialectic, by standing the doctrine of its Hegelian predecessor on its head, was no less negative or pitilessly destructive than its Nietzschean counterpart: “In accordance with the Hegelian method of thought, the proposition of the rationality of everything that is real dissolves to become the opposite proposition: All that exists deserves to perish. But precisely therein lay the true significance and the revolutionary character of Hegelian philosophy, that it once and for all dealt the deathblow to the finality of all products of human thought and action.”[75] Moreover, the concept of freedom was always understood by Marx as the freedom to become what one will be, rather than the ontological notion of freedom promulgated by romanticism and postmodernism as the freedom to be (e.g., a Jew or a Muslim, a sculptor or a painter, heterosexual or homosexual) what one already “is.” Marx saw this possibility for self-becoming as grounded in the historical emergence of the capitalist mode of production, which, after establishing itself, reproduces the conditions of its own existence, as well as those conditions by which it might be superseded:

[Capitalism’s] presuppositions, which originally appeared as conditions of its becoming — and hence could not spring from its action as capital — now appear as results of its own realization, reality, as posited by it — not as conditions of its arising, but as results of its presence. It no longer proceeds from presuppositions in order to become, but rather it is itself presupposed, proceeding from itself to create the conditions of its maintenance and growth…This correct view [of its development] leads at the same time to the points at which the suspension of the present form of production relations gives signs of its becoming — foreshadowings of the future. Just as, on one side, the pre-bourgeois phases appear as merely historical, suspended presuppositions, so do the contemporary conditions of production likewise appear as engaged in suspending themselves and hence also as positing the historic presuppositions for a new state of society.[76] Continue reading

![]() .

.

Image: Anti-Dühring

and Anti-Christ

![]()

.

Return to the introduction to “Twilight of the idoloclast? On the Left’s recent anti-Nietzschean turn”

Return to “Malcolm Christ, or the Anti-Nietzsche”

In his defense, Bull is hardly the first to have made this mistake. Many of Nietzsche’s latter-day critics, self-styled “progressives,” actually share his vulgar misconception of socialism. The major difference is that where Nietzsche vituperated against the leveling discourse of equality, believing it to be socialist, his opponents just as gullibly affirm it — again as socialism. Noting that Nietzsche’s antipathy toward the major currents of socialism he encountered in his day was an extension of his scorn for Christianity and its “slave morality,” which he saw apotheosized in the modern demand for equality, some critics go so far as to uphold not only the equation of socialism with equality, but also to defend its putative precursors in traditional religious practices and moral codes. This is of a piece with broader attempts by some Marxists to accommodate reactionary anti-capitalist movements that draw inspiration from religion, whether this takes the form of apologia for “fanaticism” (as in Alberto Toscano’s Fanaticism),[48] “fundamentalism” (as in Domenico Losurdo’s “What is Fundamentalism?”),[49] or “theology” (as in Roland Boer’s trilogy On Marxism and Theology).[50] These efforts to twist Marxism into a worldview that is somehow compatible with religious politics ought to be read as a symptom of the death of historical Marxism and the apparent absence of any alternative.

According to the testimony of Peter D. Thomas, “[Losurdo] argues that Nietzsche’s…critiques of Christianity…were a response to the role [it] played in the formation of the early socialist movement. The famous call for an amoralism, ‘beyond good and evil,’ is analyzed as emerging in opposition to socialist appeals to notions of justice and moral conduct.”[51] Corey Robin touches on a similar point in his otherwise uninspired psychology of “the” reactionary mind, a transhistorical mentalité across the centuries (from Burke to Sarah Palin, as the book’s subtitle would have it): “The modern residue of that slave revolt, Nietzsche makes clear, is found not in Christianity, or even in religion, but in the nineteenth-century movements for democracy and socialism.”[52] Finally, Ishay Landa differentiates between Marxist and Nietzschean strains of atheism in his 2005 piece “Aroma and Shadow: Marx vs. Nietzsche on Religion,” in which he all but confirms the latter’s suspicion that socialism is nothing more than a sense of moral outrage against empirical conditions of inequality.[53]

To make better sense of this confusion, it is useful to glance at the various texts and authors that Nietzsche took to be representative of socialism. Once this has been accomplished, the validity of his claim that nineteenth-century socialism was simply the latest ideological incarnation of crypto-Christian morality, repackaged in secular form, can be ascertained. Notwithstanding the incredulity of Losurdo,[54] even the German Social-Democrat and later biographer of Marx, Franz Mehring, who had little patience for Nietzsche (despite his indisputable poetic abilities), confessed: “Absent from Nietzsche’s thinking was an explicit philosophical confrontation with socialism.”[55] (Mehring added, incidentally, much to Lukács’ chagrin, that “[t]he Nietzsche cult is…useful to socialism…No doubt, Nietzsche’s writings have their pitfalls for young people…growing up within the bourgeois classes…, laboring under bourgeois class-prejudices. But for such people, Nietzsche is only a transitional stage on the way to socialism.”[56] Other than the writings of such early socialists as Weitling and Lamennais, however, Nietzsche’s primary contact with socialism came by way of Wagner, who had been a follower of Proudhon in 1848 with a streak of Bakuninism thrown in here and there. Besides these sources, there is some evidence that he was acquainted with August Bebel’s seminal work on Woman and Socialism. More than any other, however, the writer who Nietzsche most associated with socialist thought was Eugen Dühring, a prominent anti-Marxist and anti-Semite. Dühring was undoubtedly the subject of Nietzche’s most scathing criticisms of the maudlin morality and reactive sentiment in mainstream socialist literature. Continue reading

Notes to Twilight of the idoloclast? On the Left’s recent anti-Nietzschean turn, Malcolm Christ, or the Anti-Nietzsche, Anti-Dühring and Anti-Christ: Marx, Engels, Nietzsche

[1] “Reading for victory is the way Nietzsche himself thought people ought to read.” Bull, Malcolm. Anti-Nietzsche. (Verso Books. New York, NY: 2011).

[2] As Domenico Losurdo blurbs on the back of his book, “Altman…adopts Nietzsche’s own aphoristic genre in order to use it against him.” Altman himself explains: “[T]he whole point of writing in Nietzsche’s own style was to demonstrate how much power over his readers he gains by plunging him into the midst of what may be a pathless ocean, confusing them as to their destination.” Altman, William. Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche: The Philosopher of the Second Reich. (Lexington Books. New York, NY: 2012). Pg. xi. Later Altman admits, however, that “[t]his kind of writing presumes, of course, good readers.” Ibid., pg. 181.

[3] Dombrowsky, Don. Nietzsche’s Machiavellian Politics. (Palgrave MacMillan. New York, NY: 2004). Pg. 134.

[4] Conway, Daniel. Nietzsche and the Political. (Routledge. New York, NY: 1997). Pg. 119.

[5] Appel, Fredrick. Nietzsche Contra Democracy. (Cornell University Press. Ithaca, NY: 1999). Pg. 120.

[6] “[I]n uncovering Nietzsche’s rhetorical strategy [they] reuse it.” Bull, Anti-Nietzsche. Pg. 32.

[7] Ibid., pg. 33.

[8] Ibid., passim, pgs. 35-38, 42, 47-48, 51, 74-76, 98, 100, 135, 139, 143.

……Indeed, Bull’s call to “read like a loser” grants to the essays in Anti-Nietzsche their hermeneutic integrity. This formulation has since gone on to become one of the book’s most celebrated phrases, as well, charming reviewers from New Inquiry’s David Winters to Costica Bardigan of the Times Higher Education. Winters, David. “Reading Like a Loser.” New Inquiry. (February 14, 2012). Bardigan, Costica. “Review of Malcolm Bull’s Anti-Nietzsche.” Times Higher Education. (January 29, 2012). Even longtime admirers of Nietzsche like T.J. Clark admit its interpretive power: “[N]o other critique of Nietzsche, and there have been many, conjures up the actual reader of Daybreak and The Case of Wagner so unnervingly.” Clark, T.J. “My Unknown Friends: A Response to Malcolm Bull.” Nietzsche’s Negative Ecologies. (University of California Press. Berkeley, CA: 2009). Pg. 79. Continue reading

In the sixties a certain confusion exists in contemporary architecture, as in painting; a kind of pause, even a kind of exhaustion. Everyone is aware of it. Fatigue is normally accompanied by uncertainty, what to do and where to go. Fatigue is the mother of indecision, opening the door to escapism, to superficialities of all kinds.

A symposium at the Metropolitan Museum of New York in the spring of 1961 discussed the question, “Modern Architecture, Death or Metamorphosis?” As this topic indicates, contemporary architecture is regarded by some as a fashion and — as an American architect expressed it — many designers who had adopted the fashionable aspects of the “International Style,” now found the fashion had worn thin and were engaged in a romantic orgy. This fashion, with its historical fragments picked at random, unfortunately infected many gifted architects. By the sixties its results could be seen everywhere: in small-breasted, gothic-styled colleges, in a lacework of glittering details inside and outside, in the toothpick stilts and assembly of isolated buildings of the largest cultural center.

A kind of playboy-architecture became en vogue: an architecture treated as playboys treat life, jumping from one sensation to another and quickly bored with everything. I have no doubt that this fashion born out of an inner uncertainty will soon be obsolete; but its effects can be rather dangerous, because of the worldwide influence of the United States.

We are still in the formation period of a new tradition, still at its beginning. In Architecture, You and Me I pointed out the difference between the nineteenth- and twentieth-century approach to architecture. There is a word we should refrain from using to describe contemporary architecture — “style.” The moment we fence architecture within a notion of “style,” we open the door to a formalistic approach. The contemporary movement is not a “style” in the nineteenth-century meaning of form characterization. It is an approach to the life that slumbers unconsciously within all of us.

In architecture the word “style” has often been combined with the epithet “international,” though this epithet has never been accepted in Europe. The term “international style” quickly became harmful, implying something hovering in mid-air, with no roots anywhere: cardboard architecture. Contemporary architecture worthy of the name sees its main task as the interpretation of a way of life valid for our period. There can be no question of “Death or Metamorphosis,” there can only be the question of evolving a new tradition, and many signs show that this is in the doing.

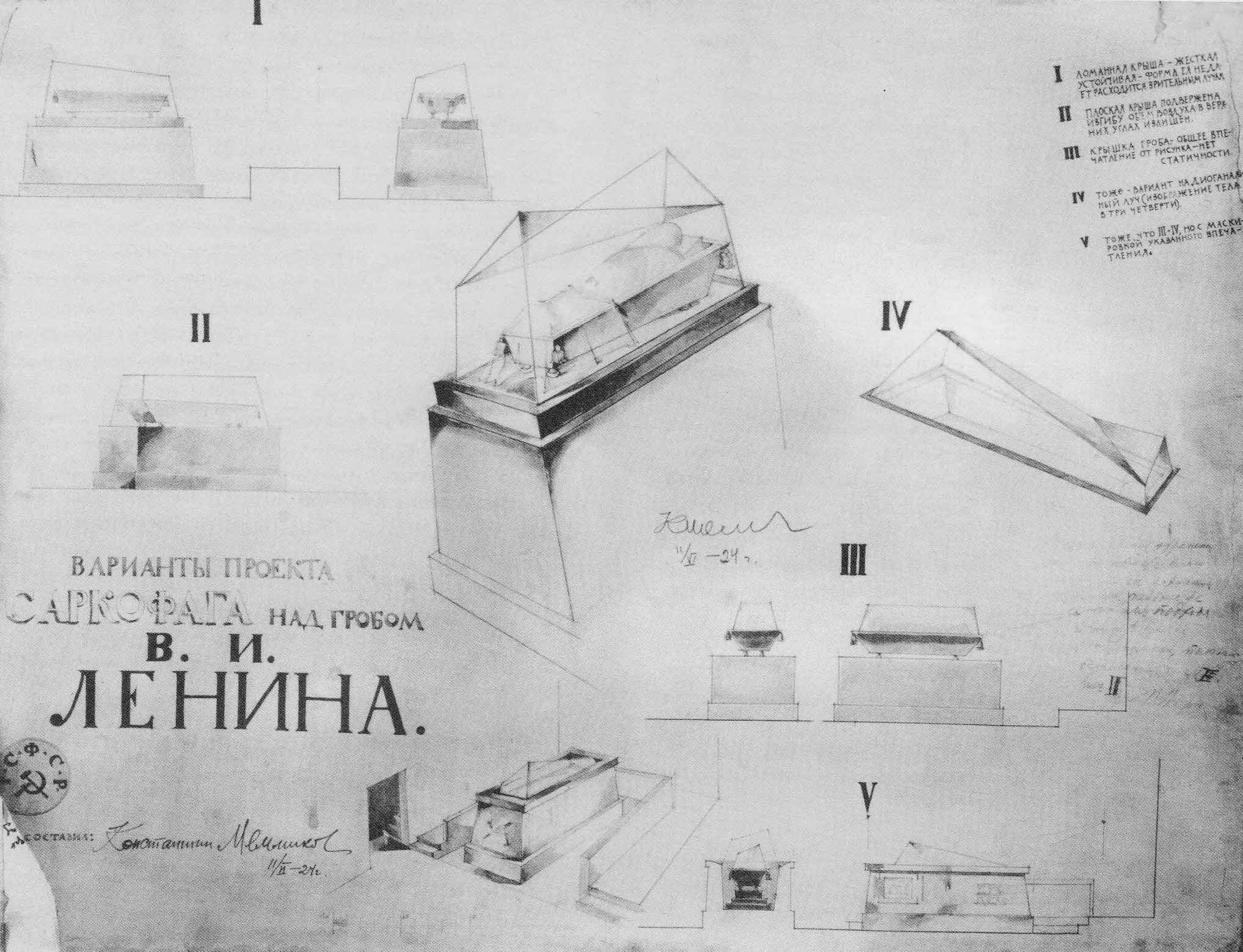

The architectural modernist Konstantin Mel’nikov’s prismatic Variations on the project of Lenin’s sarcophagus (1924), proposed but never realized. Continue reading

![]() .

.

Image: Photograph of Wilhelm Dilthey

Go to Three models of “resistance” — Introduction

In 1890, the German philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey authored a remarkable essay on “The Origin of Our Belief in the Reality of the External World and Its Justification.” Against some of the prevailing interpretations of his day, Dilthey argued that the reality of the external world was neither an immediately given fact of consciousness nor the product of unconscious inferences linking cause to effect. On the contrary, he asserted that the reality of the world outside of the self comes to be known to individual subjects only by encountering resistance [Widerstand] to the will. Recognition of the external world’s reality thus arises from “[the] consciousness of voluntary motion [entering] into a relation with the experience of resistance [Widerstandserfahrung]; in this way a…distinction develops between the life of the self and something other that is independent of it.”[10]

Resistance in this model stands as the original ground on which all subsequent differentiation takes place. Here the “I” is first separated off from a “not-I” that opposes it. But unlike the Fichtean philosophy from which these terms are derived,[11] “I” and “not-I” for Dilthey are not distinguished (at least initially) by an act of cognition. This cleavage is first realized, rather, through an act of volition. In other words, the intuition of a world that exists apart from the ego does not come about through the self-positing activity of the subject in making itself an object of contemplation or thought,[12] as in Fichte. It manifests itself through an act of the will, in the subject’s efforts to subjugate the whole of reality unto itself — thereby satisfying its every appetite. The “pushback” it experiences in trying to enforce its will then prompts an awareness that something exists outside the self. Thus does consciousness enter into existence, circumscribed within a world that is not of its making. It learns the limits to its own subjective agency by encountering resistance to its sovereign will.

For Dilthey, then, this experience not only formed the basis for understanding the world as an independent and objective entity — i.e., as something separate from the self. It was also to an equal extent the source of the ego’s self-understanding as an autonomous and subjective entity. Dilthey went on to explain that “the difference between a ‘self’ and an ‘other’ is first experienced in impulse and resistance…,the first germ of the ego and the world and of the distinction between them.”[13] This initial moment of separation is then necessary to lend legitimacy and significance to the network of distinctions educed from it. “The entire meaning of the words ‘self’ and ‘other,’ ‘ego’ and ‘world,’” explained Dilthey, “and the differentiation of the self from the external world is contained in the experiences of our will and of the feelings connected with it…The core of this distinction is…the relationship of impulse and restraint of intention, of will and resistance.”[14] Continue reading

A Platypus teach-in by Ross Wolfe and Sammy Medina meant to explore some issues connected to the “Ruins of Modernity: The failure of revolutionary architecture in the 20th century,” an upcoming panel event at NYU featuring Peter Eisenman, Reinhold Martin, Joan Ockman, and (hopefully) Bernard Tschumi.

This presentation will touch on modernist architecture’s attempt to address problems like the housing shortage, the poor living conditions of the urban proletariat, and the liberation of woman from domestic slavery. Approaches to homelessness past and present: the 1920s-1930s Social-Democratic utopia of the Siedlung vs. the 1990s-2000s anarchist utopia of the Squat. Housing the unemployed and underemployed — the so-called “reserve army of labor” or “surplus population” — from the sotsgorod to Occupy Your Home.

A room, or perhaps a “pod,” of one’s own, and its importance for modern bourgeois subjectivity. Annihilating the antithesis between town and country (Karl Marx, Ebenezer Howard, Mikhail Okhitovich), the absurdity of the nuptial bed (Karel Teige), the city of children (Leonid Sabsovich), and the creation of a hermaphroditic humanity (El Lissitzky).

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/53579139]

A panel event held at the New School in New York City on November 14th, 2012.

Loren Goldner ┇ David Harvey ┇ Andrew Kliman ┇ Paul Mattick

What does it meant to interpret the world without being able to change it?

Featuring:

• LOREN GOLDNER

// Chief Editor of Insurgent Notes; ┇ Author: — Ubu Saved From Drowning: Class Struggle and Statist Containment in Portugal and Spain, 1974-1977 (2000), — “The Sky Is Always Darkest Just Before the Dawn: Class Struggle in the U.S. From the 2008 Crash to the Eve of Occupy” (2011)

• DAVID HARVEY

// Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and Geography at the CUNY Grad Center; ┇ Author: — The Condition of Postmodernity (1989), — A Brief History of Neoliberalism (2005), — “Why the US Stimulus Package is Bound to Fail” (2008) — The Enigma of Capitalism (2010)

• ANDREW KLIMAN

// Professor of Economics at Pace University; ┇ Contributing author to the Marxist-Humanist Initiative’s (MHI’s) With Sober Senses since 2009; ┇ Author: — Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency (2007), — The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the “Great Recession” (2012)

• PAUL MATTICK

// Chair of the Department of Philosophy at Adelphi University; ┇ Contributor to The Brooklyn Rail ┇ Author: — Social Knowledge: An Essay on the Nature and Limits of Social Science (1986), — Business as Usual: The Economic Crisis and the Failure of Capitalism (2011)